From the moment they are born, babies look to caregivers to help them learn, develop and thrive. Positive relationships with caregivers are vital for promoting a young child’s brain development, well-being and mental health. Whether a parent, grandparent or other caring adult, caregivers play the most important role in supporting the physical, emotional and cognitive development of children. But parenting is not an easy job and, as any caregiver knows, it doesn’t come with an instruction manual.

Parents’ ability to be the best caregivers they can be is also shaped by their experiences and well-being. This is why parenting interventions and early childhood development (ECD) programmes need to focus not only on the holistic development of children, but also on caregivers themselves. Research shows that ECD interventions that include an element directed at caregivers – by providing information on positive caregiving practices or by otherwise supporting parental well-being (caring for the caregiver) – have been successful in improving outcomes for children, including when the information is provided in person or remotely, via text messages or phone calls. And these interventions may provide an even greater return on investment by supporting the whole family. Emerging evidence shows that it’s not just children who benefit from ECD programmes – caregivers can benefit too, through improved mental health outcomes.

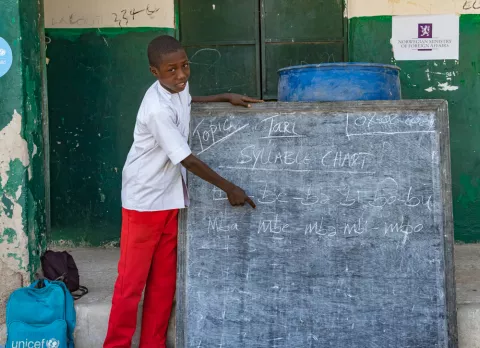

Examples from around the world highlight the importance of ECD programmes in promoting well-being in both children and their caregivers. Many of these examples focus on promoting play, a key tool for supporting child and caregiver mental health. For example, in Ghana, the NGO Lively Minds trained mothers of four- and five-year-olds on child-friendly educational games and teaching practices, emphasizing the importance of education and play. The intervention improved children’s cognition while boosting mothers’ self-esteem and mental health.

In Uganda, the NGO Plan Uganda offered peer-led group sessions on childcare and maternal well-being to mothers and fathers, including interactive activities and home visits for personalized discussion. Children whose parents participated had higher cognitive outcomes than children whose parents didn’t, and their mothers also reported lower rates of depression. In Pakistan, an initiative called Learning through Play Plus focused on empowering caregivers with playful learning techniques. The intervention improved children’s socio-emotional development and reduced maternal depression.

In a survey of families from Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates who watched Ahlan Simsim (a locally produced, Arabic-language version of Sesame Street for children in the Syrian response region), 79 per cent of parents said the show’s emotional vocabulary lessons helped them learn new ways to name their own emotions. Eighty-five per cent reported that the show’s lessons had helped them learn to manage their emotions in difficult moments.

In each of these examples, child outcomes improved along educational and emotional dimensions. But, importantly, these ECD interventions didn’t just affect children – they also improved caregiver mental health.

Acting early to support children and caregivers is the best investment governments can make to promote mental health and other developmental outcomes for the whole family. This is particularly important in humanitarian settings where early support for children, families, and communities is needed to address the immediate and long-term repercussions of crises. For example, at border crossings into countries neighbouring Ukraine, UNICEF and UNHCR, jointly with local authorities and partners, established Blue Dots hubs, safe spaces which provide information and services including counselling and psychosocial support to children, parents and caregivers, as well as referral services to connect refugee families who have experienced violence to additional support.

As in this example, the approach to supporting families’ mental health needs must be multifaceted, reaching them through multiple avenues. As such, ECD efforts should complement – not replace – other targeted mental health interventions. Advocates for both mental health and the importance of ECD are calling for actors to:

- Prioritize a caregiver support component of ECD programmes to provide all caregivers with awareness, skills, and support to build nurturing relationships with their children – and scale up these efforts where possible.

- Ensure that all ECD programmes have a strong mental health component, addressing both child and caregiver mental health and well-being.

- Increase investment in dedicated mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) programmes for children and caregivers, particularly in crisis settings.

Organizations around the world – including Sesame Workshop, UNICEF and our partners – are working to bring the needs of the youngest children into the spotlight. Ultimately, supporting children means supporting caregivers too. ECD programmes can and should serve the whole family – and can have lasting positive benefits for the whole family in return.

About the authors:

Sam Friedlander is Advocacy and Policy Specialist, Sesame Workshop.

Benjamin Perks is Head of Advocacy, UNICEF.

Oluwatosin Akingbulu is Advocacy and Communication Specialist, UNICEF.

Chemba Raghavan is Senior Advisor for Early Childhood Development, UNICEF.

With contributions from Emma Ferguson, Mental Health Global Advocacy Lead, UNICEF.